By making clever use of a special quantum property of electrons, researchers at the American University of Colorado Boulder have managed to make their so-called rectennas, which are too small to see with the naked eye, more than 100 times more efficient than comparable heat. energy-producing devices. They published their results on Tuesday in Nature Communications.

Rectennas work just like radio antennas. But instead of radio waves, they capture heat radiation. Those electromagnetic waves cause alternating electrical currents in antennas. At the end of antennas is a so-called diode that converts this alternating current into direct current, which you can then use for your computer, TV or other devices.

It sounds simple but is tricky. Heat radiation has a high frequency: a trillion vibrations per second. To receive this high-frequency radiation, the antennas have to be much smaller and the diodes much faster. “In our research, we focused on making the fastest possible diode,” says Amina Belkadi, who recently obtained her PhD in rectenne research.

Electrons in a tunnel

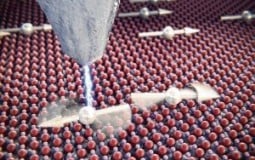

The researchers use minuscule rectennas a few thousandths of a millimeter in size. The diode is only a few hundred thousandths of a millimeter in size. “The diode consists of two metals with an insulating material in between,” says Belkadi. The electrons that make up the generated current must make their way through the insulating layer to provide usable direct current. In current diodes, where the insulator consists of one material, the electrons experience a lot of resistance, which makes them difficult to move and ultimately produces little electricity.

A few decades ago, theorists predicted that a special quantum effect, resonant tunneling, occurs when you replace the single insulating layer with two or more different layers. “If you use multiple layers, electrons at certain energy levels can shoot through the material almost without resistance,” says Belkadi. The effect, as it were, creates a ‘tunnel’ through which the electrons move easily from one side to the other.

“The theory didn’t predict exactly which materials to use,” continues Belkadi. “During my PhD I played with different materials of different thicknesses. Ultimately we arrived at a diode with two insulating layers a few millionths of a millimeter thick: nickel oxide and aluminum oxide.” To test the special quantum effect, the researchers made two sets with a quarter of a million rectennas each. One set had a single insulating layer of nickel oxide, the other had the two layers. Only the set with the two layers turned out to be able to generate a measurable amount of electricity from heat radiation. The quantum effect worked. Although only one percent of the heat energy was converted into electricity in the test.

“It is a great step forward,” says Huib Visser, professor at Eindhoven University of Technology and not involved in the research. “But the road to commercialization will take some time. For example, attention will also be needed to improve the antennas.” Belkadi agrees: “Efficiency is far from what we want and what is needed to make a profitable commercial device. But we have come closer to that goal.”